Files and file research

Files are of great importance in the reappraisal of compulsory social measures and placements. In addition to interviews with those affected, they are a key source of information for research in order to investigate the practices of authorities, courts and institutions. Affected persons also have the right to access their personal files. If they apply to the Federal Office of Justice for a solidarity contribution, files can serve as important evidence of the injustice they suffered.

Legal basis for file research

In connection with compulsory social measures and placements prior to 1981, the right to access files has been regulated in the CSMPA (The Federal Act on Compulsory Social Measures and Placements prior to 1981) since 2017. The data protection and archive laws of the Confederation and cantons also constitute the basis for the inspection of files. In accordance with the CSMPA, the cantonal contact points and the cantonal archives support affected persons in the search for their files. Those affected are given easy and free access to their files. They also have the right to mark data as disputed if they wish to correct the content. Relatives can also access the files, provided the affected person has given their consent or is already deceased. The CSMPA also stipulates that files on compulsory social measures and placements must be retained.

Opportunities and risks of file access for those affected

Affected persons request to access their files for different reasons. Some want to learn more about their past, others are searching for relatives, or wish to understand who was responsible for their removal from the family and why their voices were ignored. Often, the files are the only material traces left from their childhood. They can also contain important biographical information.

However, accessing their files is an ambivalent matter for many. Reading the documents is time-consuming and it is often difficult to find the narrative thread in hundreds of pages of files. For many affected persons, only a few files have survived, and large gaps remain. In addition, many processes are unclear, and the context can only be understood with great effort. The contents and scope of the files can vary greatly depending on who created the documents at the time. In most cases, the files are kept in different places and must be gathered. In the copies of the files handed over by archives or institutions, names or entire passages are sometimes blacked out due to the need to protect the interests of third parties. It is therefore important for the issued copies of files to be explained.

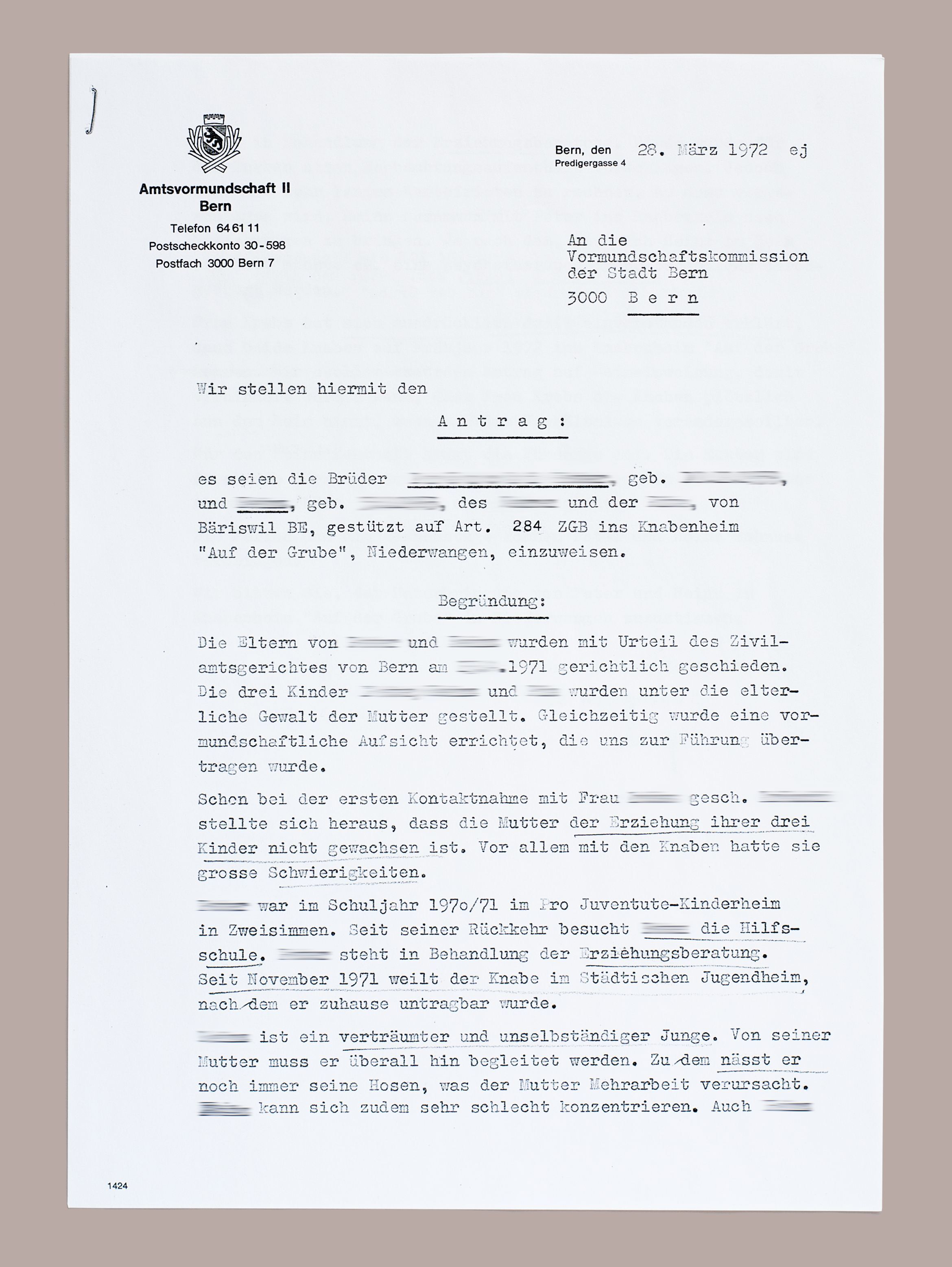

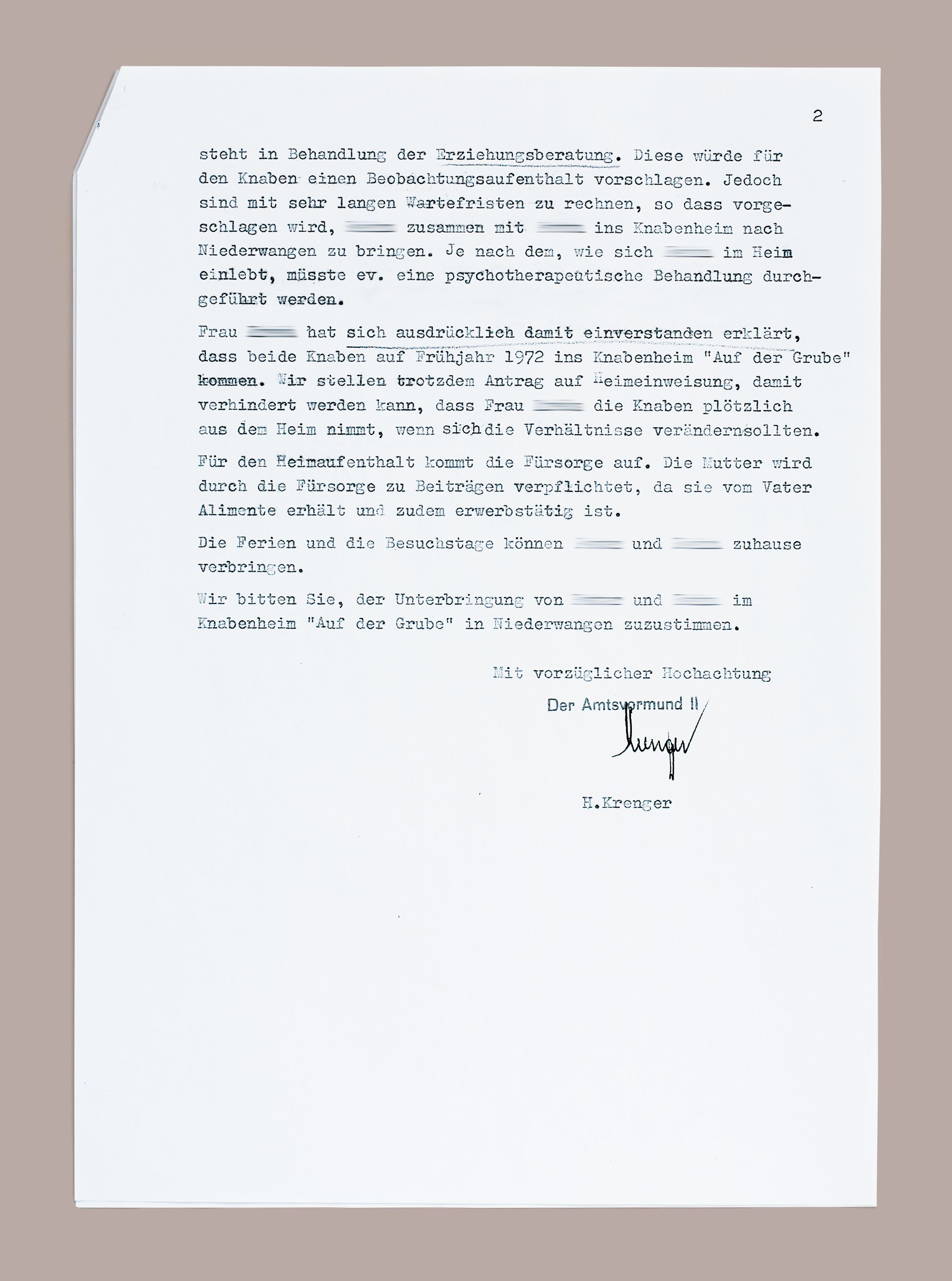

Finally, the files also contain degrading assessments of affected persons. They are labelled “psychopaths” and “imbeciles”, others are accused of “pathological deceitfulness”, and young women in particular are described as being “morally endangered”. Such attributions can still be deeply hurtful even decades later and may trigger fear of renewed official intervention. Research has shown that reading such violent language can also lead to re-traumatisation. Support from relatives, specialists or contact points is therefore essential.

Stigmatisation and discrimination through record-management

Files were and remain an important administrative tool. On the one hand, files provide legal protection because they make it possible to trace government actions and official decisions. On the other hand, files can also contribute to the stigmatisation of people through discriminatory wording and negative statements about them. This can lead to serious discrimination, such as an unjustified order for guardianship. Files not only depict actions but also create realities. They were the basis for highly consequential decisions. For example, the guardianship authorities or courts responsible at the time made their decisions mainly based on reports from involved offices or consultations with officials, in many cases without having heard the affected person’s testimony themselves.

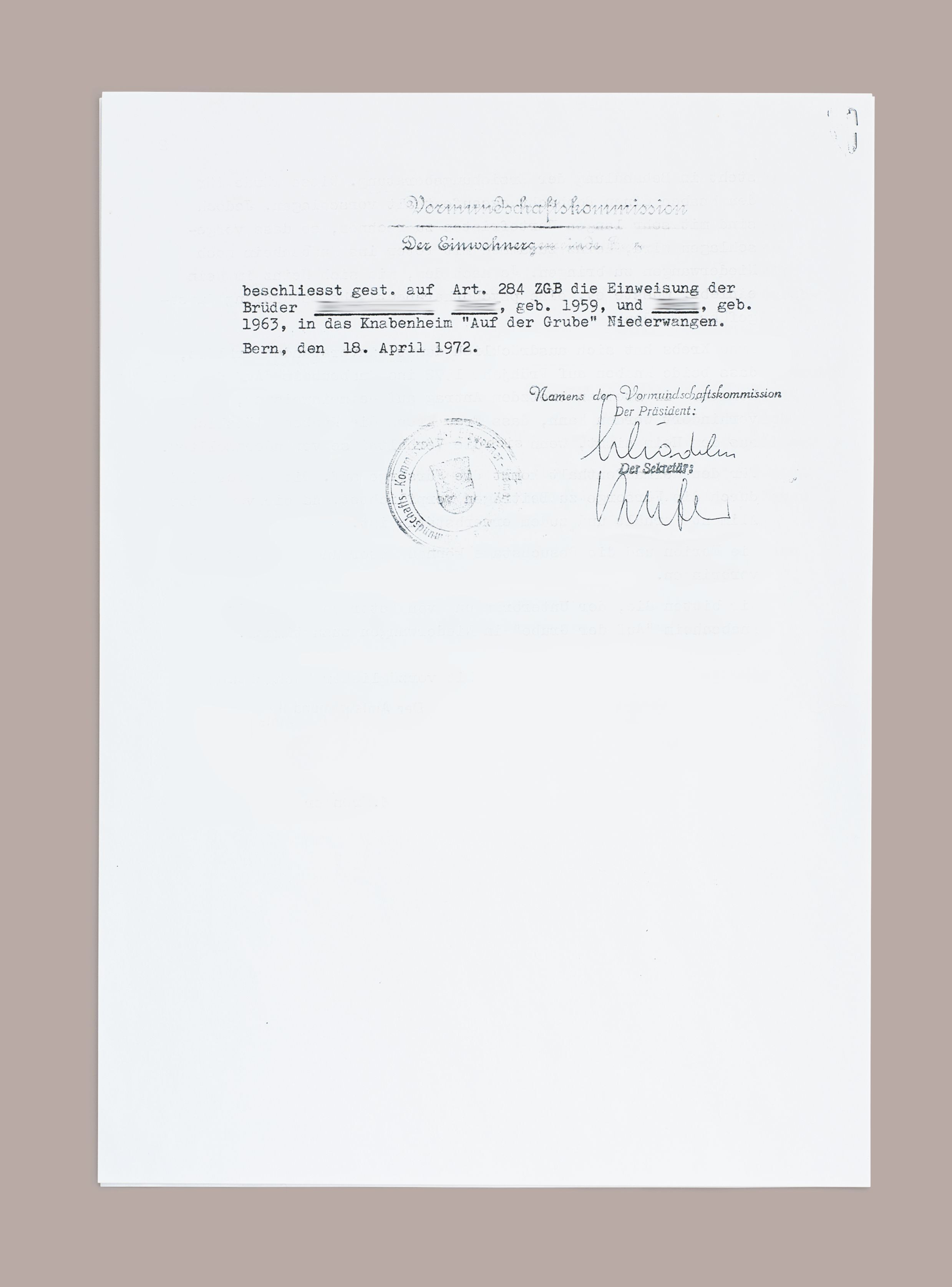

Guardianship removal decision by the Bern Official Guardianship Authority, 1972, page 1.

Source: private collection.

Guardianship removal decision by the Bern Official Guardianship Authority, 1972, page 2.

Source: private collection.

Guardianship removal decision by the Bern Official Guardianship Authority, 1972, page 3.

Source: Private collection.

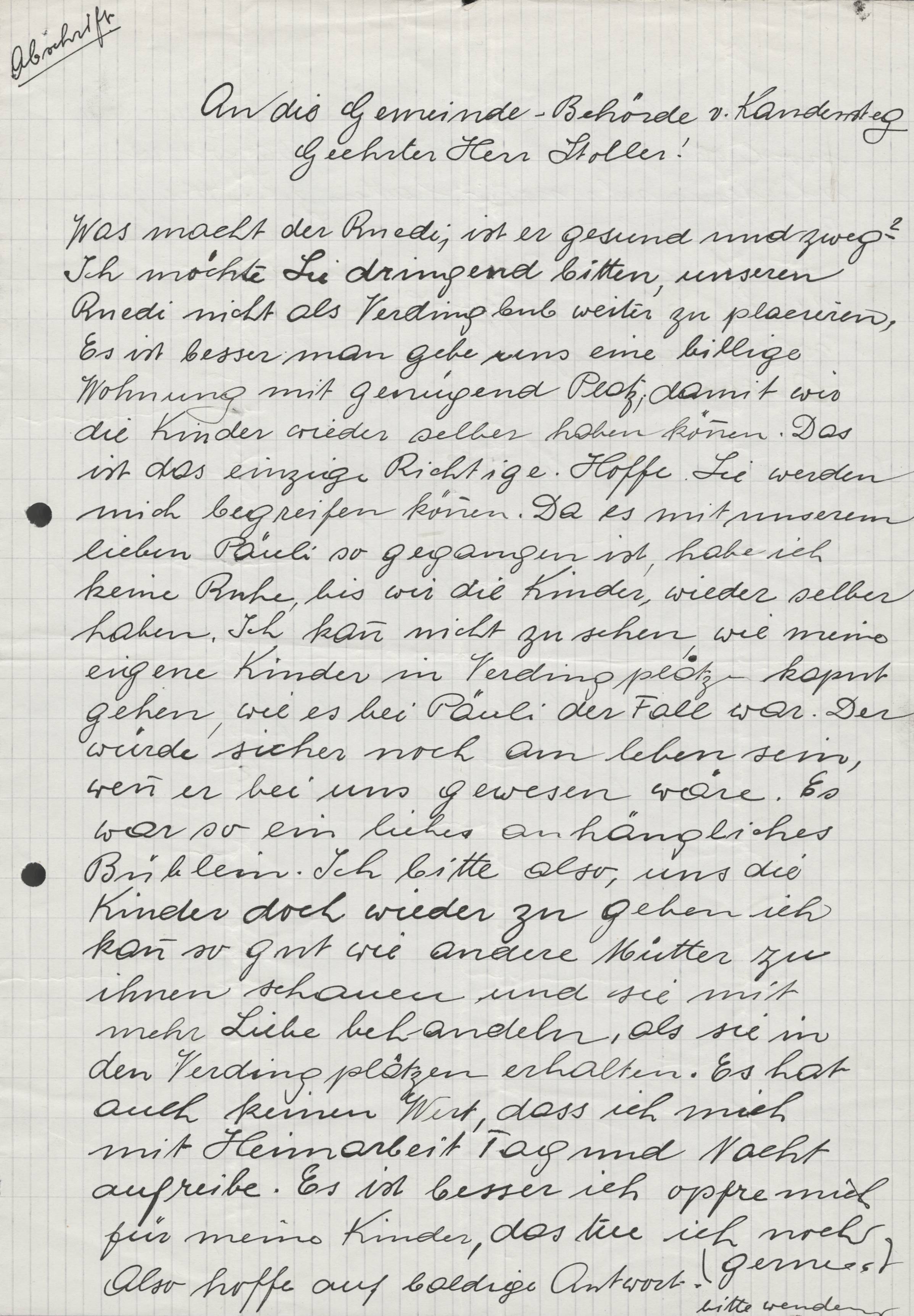

Letter from a mother, 1945.

Transcript of a letter from a mother whose child was indentured and died.

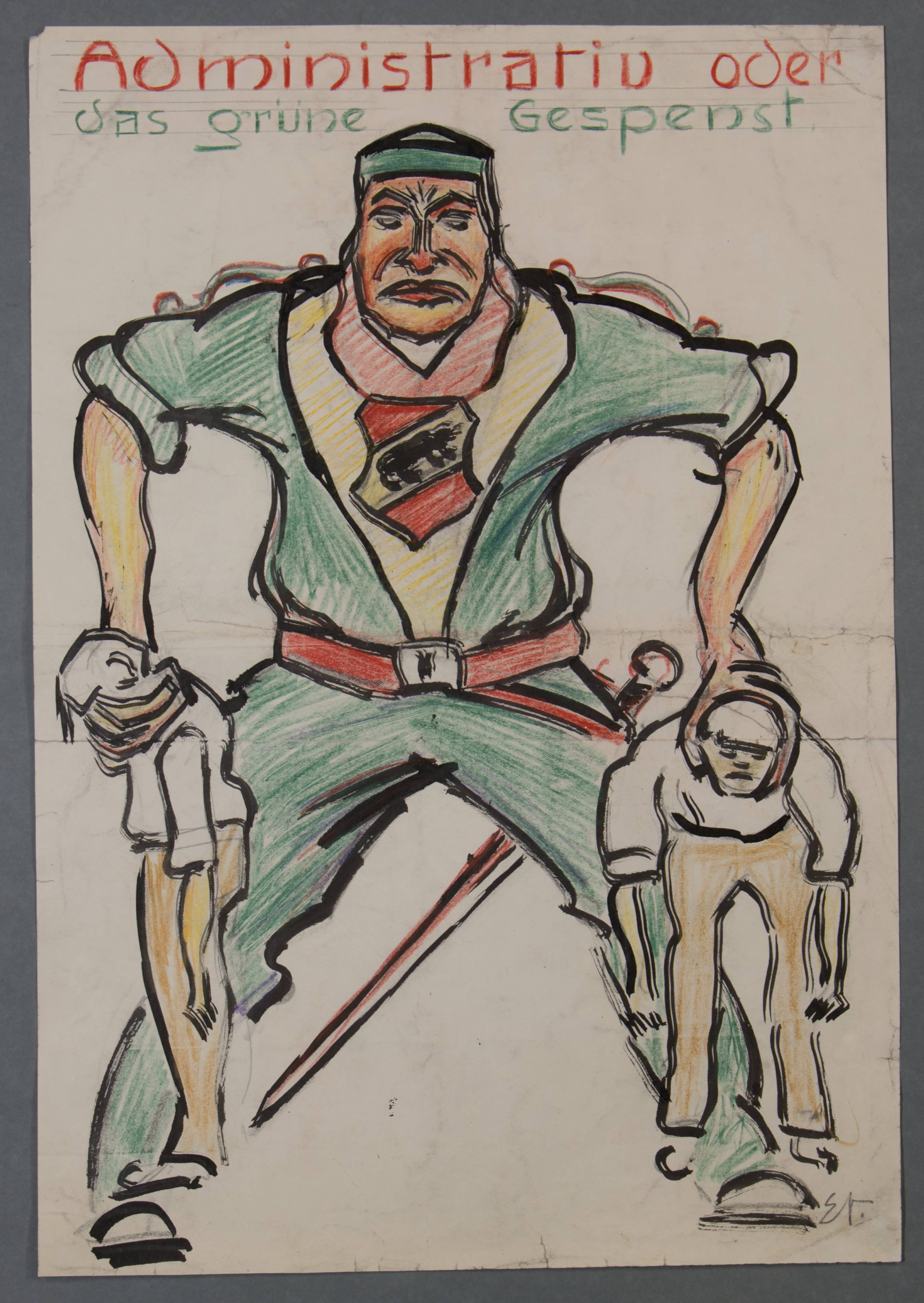

Administrative or the green spectre. Witzwiler Illustrierte, 1st year, December 1929.

An interned artist recounts everyday life in the Witzwil labour camp with colourful caricatures. The artist is believed to be Emil Rudolf Neuenschwander, who wassubject to administrative detention several times for ‘dissolute behaviour’.

Image: probably Emil Rudolph Neuenschwander. Source: Witzwiler-Illustrierte (Vorlagen, Arbeiten von Gefangenen), Jahrgang 1, Dezember 1929, Staatsarchiv des Kantons Bern, BB 4.2.248.

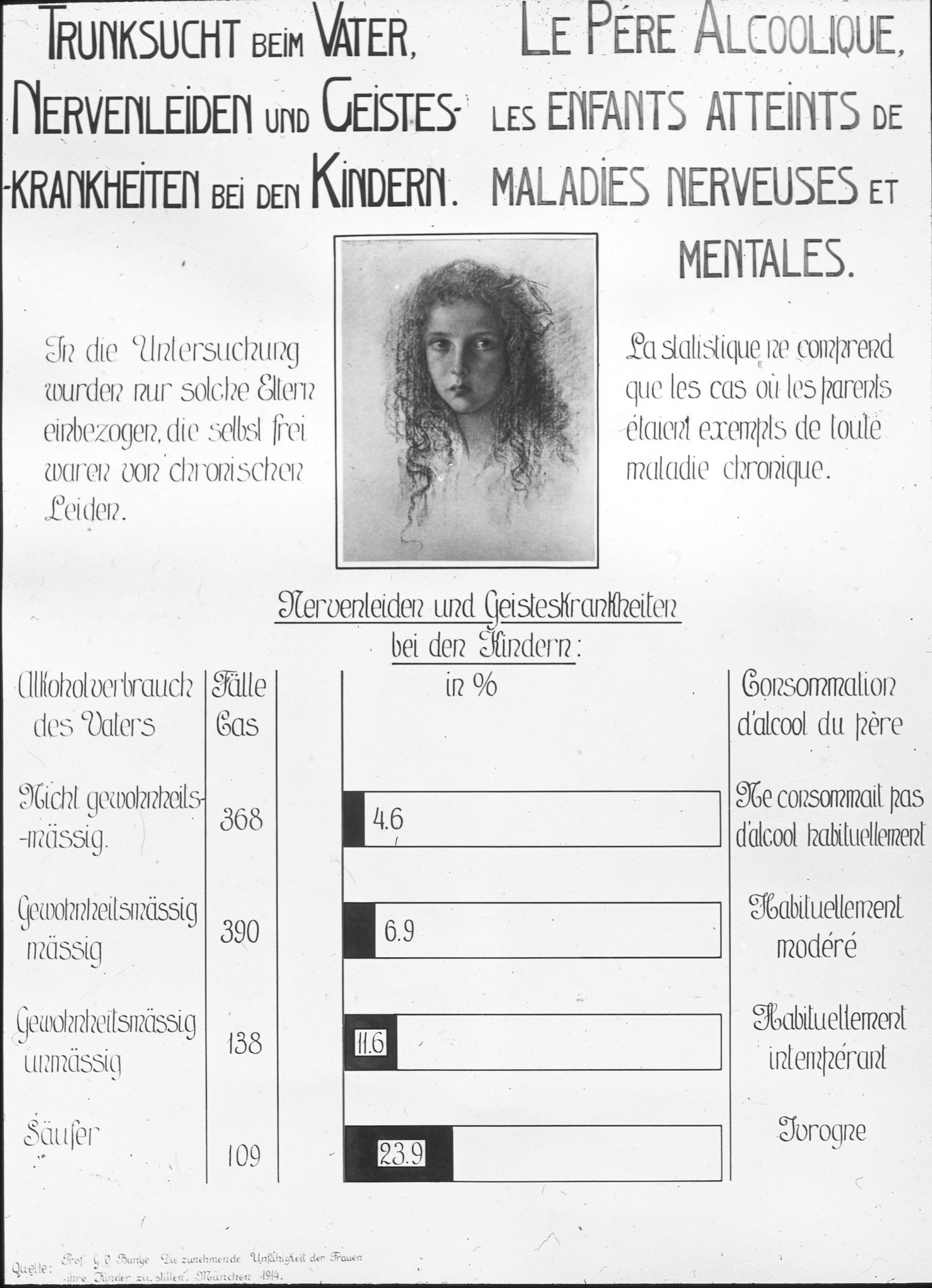

Nervous disorders and mental illness in children. 1930.

Series of slides on infant care. ‘Alcoholism in fathers, nervous disorders and mental illness in children. Only parents who were themselves free of chronic conditions were included in the study.’ Graph showing ‘Nervous disorders and mental illness in children in %’ depending on ‘father's alcohol consumption’.

In the files that circulated between authorities, guardians and homes, assumptions quickly became accepted facts. This was also since the right to inspect files was handled restrictively for a long time. It was almost impossible to correct such negative statements or assumptions, as the individuals concerned had no knowledge of what was written about them in the files. At the same time, the files “followed” them against their will and even without their knowledge from place to place, and could affect their lives again at any time.

Access to files in transformation

Today, everyone has the right to access their own files and official documents. This is intended to ensure the transparency and traceability of government activities. Special protections apply to files containing personal data. Third parties wishing to obtain access to such files must provide justification and, in many cases, the consent of the data subject.

In the past, however, the protection of personal data was also used to obstruct or restrict research. For decades, many of those affected who were looking for answers about their personal histories faced closed doors. Only recently has the legal framework for the management and inspection of files been clearly established. The right to inspect files applies to civil, criminal and administrative proceedings. It is part of the legal right to be heard and is protected by the Federal Constitution.

Nevertheless, those affected can still encounter obstacles today when requesting access to their files. Access is sometimes refused, or those affected are told that there are no longer any files to consult. It is important in such cases to request a written justification and to seek assistance from the cantonal contact points or the federal archives. Perhaps the files were actually destroyed. Perhaps the holdings in archives are simply uncatalogued or there is a lack of knowledge of historical terminology. In such cases, the federal archives are responsible for making enquiries to local authorities and private institutions on behalf of those affected, clarifying gaps in the records and providing information on the legal basis.