Impact on affected persons

For those affected, compulsory social measures and placements often had devastating consequences that have shaped their lives ever since and that have shaped their lives ever since, with repercussions reaching into the next generations. To this day, many affected people have health or financial problems or suffer from social alienation. The thought of being restricted again, or even losing their self-determination, for example as a result of a possible need for care in old age, worries them.

Traumatic interventions in people’s lives

Over the course of their lives, affected people were often subjected to multiple forms of compulsory social measures and placements. As children, they were taken from their parents, placed in homes or foster families, re-placed several times, evaluated by professionals, sent to special classes and in some cases later detained administratively as adults. Some had already experienced violence in their families. Instead of supporting families in difficult situations, the authorities often broke them apart. In many cases, contact with parents was forbidden and siblings were separated.

Many of those affected endured terrible suffering. They could not grow up with their families, were exploited as labourers and exposed to neglect and severe violence in homes, foster or adoptive families. They were beaten, humiliated, many of them sexually abused and some even driven to suicide. Many were denied a proper school education, let alone vocational training. There were also cases of forced medication, enforced sterilisations and prevented marriages.

The presence of the past

The life stories of many affected people reflect how lonely and isolated they were and in some cases still are. After being released from a home or detention, or after guardianship was revoked, their lives were often beset by difficulties. Many lost contact with their families, were restricted in their professional activities and suffered mental or physical problems as a result of the violence they had experienced. Added to this were societal prejudices, a lack of social relationships and limited knowledge about everyday life outside institutions.

Even today, many say they find it difficult to build trust or enter relationships. Family members often met them as strangers and sometimes remained so. The files frequently contain disparaging descriptions of themselves or their families and are at the same time often the only mementos from their childhood.

The past caught up with them again and again, for example when applying for a job and having to present a CV, or when their parents were absent at their wedding. The stigma remains powerful today, and many situations are still associated with feelings of shame. This is also tied to the places and institutions where they were placed: the children’s homes, juvenile institutions, psychiatric clinics and prisons.

Impact on future generations

Their experiences also left their mark on family members, friendships and romantic relationships. Low incomes, high healthcare costs and the lack of positive role models placed additional strain on their families. Their children often describe their parents as distant, unemotional or sometimes violent. Second-generation victims repeatedly say that that their parents were unable to talk about the suffering and injustice they had experienced, or only began to do so recently. It was only when they realised and experienced that many other people had had similar experiences.

Lifelong disadvantage

Research confirms what those affected feel: in many cases, the disadvantages last a lifetime. The solidarity contribution of CHF 25,000 recognises the injustice as a symbolic act of social solidarity and allows some to fulfil a major wish for the first time. Yet it is not compensation payment that could sustainably improve their living conditions. Contributions from the federal and cantonal authorities and support from contact points cannot meet all needs. Many call for longer-term support. In old age, when they depend on care or may even be about to enter a retirement or nursing home, negative experiences from the past often resurface. Contact with authorities such as the child and adult protection authority or a medical examination can be challenging because they feel at the mercy of such professionals or do not feel taken seriously by them due to their previous experiences. Others seek support because of conflicts with relatives or strained relationships in their immediate environment. For subsequent generations too, there are only few services and opportunities to work through the past together.

The goal of a self-determined life

how people assess their current situation usually depends on whether they are able to build self-esteem and live self-determined lives despite the suffering and injustice they suffered. This usually requires enormous personal effort and, in many cases, high costs for training and therapy. For many, dealing with the past and its traumas remains a lifelong challenge.

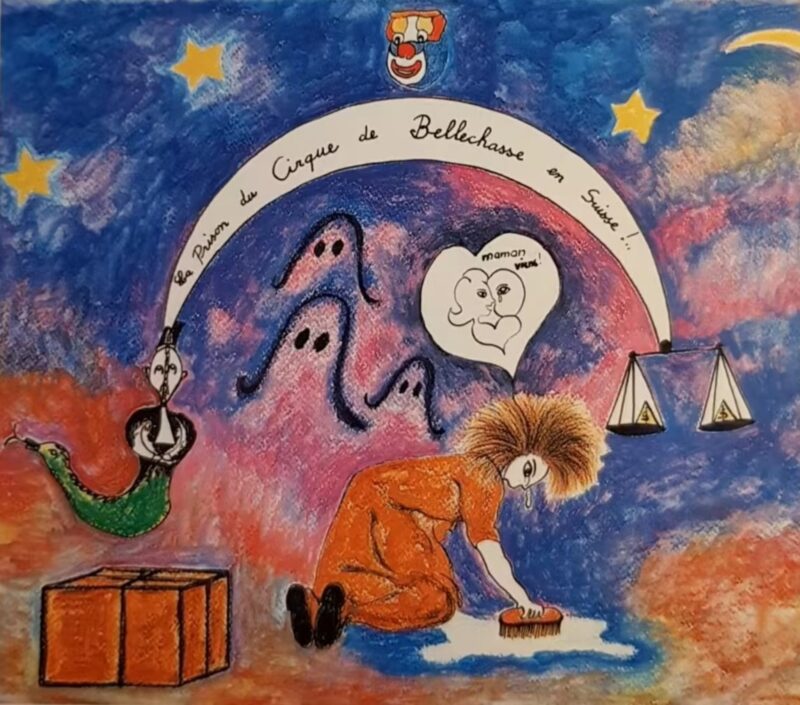

Cover image of the autobiography by Louisette Buchard-Molteni (1933-2004), which she published in 1995 under the title ‘Le tour de Suisse en cage, l'enfance volée de Louisette’ (English: Tour de Suisse in a cage, Louisette's stolen childhood). Louisette Buchard-Molteni campaigned politically, as an activist and artist against compulsory social measures and placements.