Compulsory social measures and placements. An overview

For many decades, Swiss authorities interfered in the lives of hundreds of thousands of people through “compulsory social measures and placements.” Although these measures were ostensibly intended to provide care, but in reality they resulted in immense suffering for many people. What was the origin of these measures? What were the socio-political principles that guided them? How did they change over time?

The term “compulsory social measures and placements” is an umbrella term. It refers to a variety of different measures that were applied from the 19th century until the 1970s, and in some cases even longer. The aim was to fight poverty and establish social order. These interventions affected children, adolescents, and adults. Some of them were subjected to severe psychological, physical and sexualised violence, some suffered hunger; some experienced neglect; and some were economically exploited.

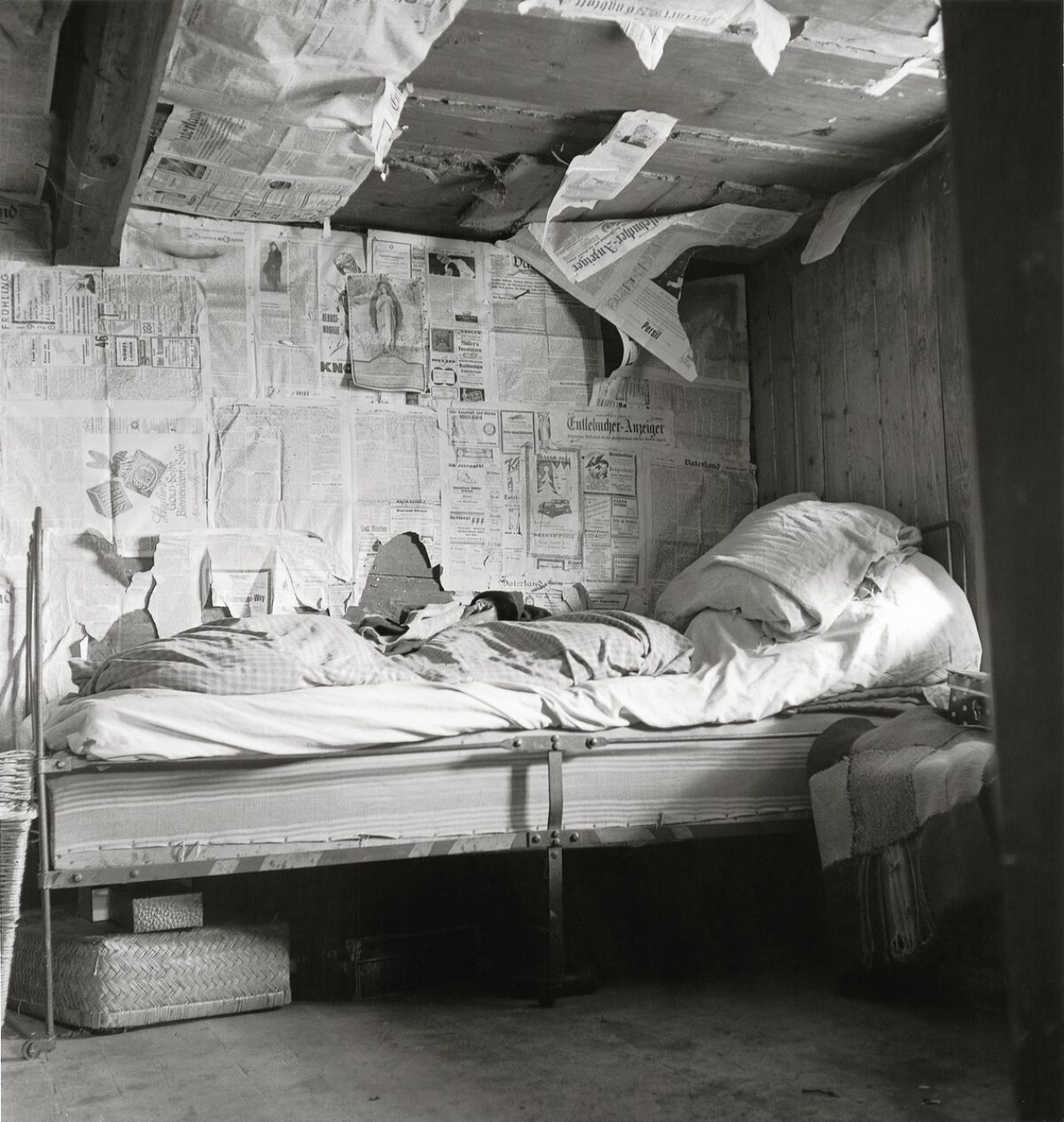

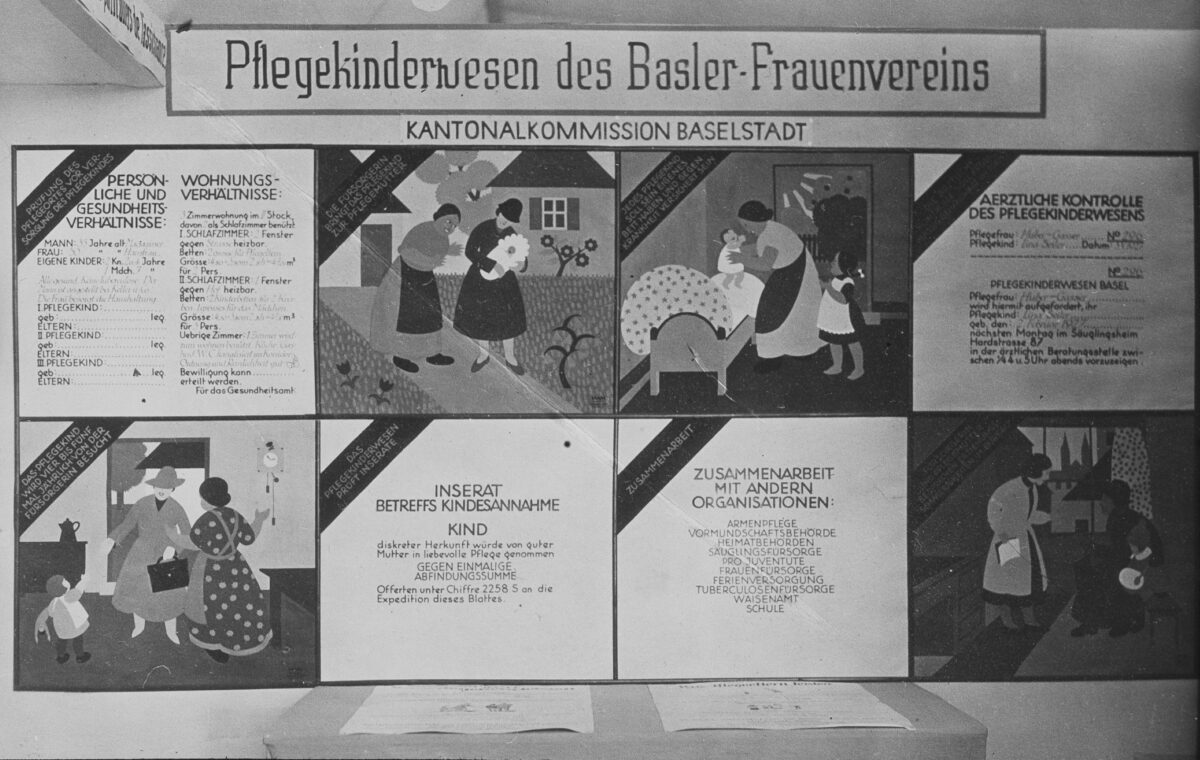

One of the most common measures was to place children and young people in homes, “reform schools” or with foster families. Some of them were made to do extremely hard labour on farms or in other businesses as so-called “contract children”, i.e. indentured child labourers. This was intended to keep the cost of their care low. Forced adoptions were also ordered. Children were permanently separated from their families against their mothers’ will, or under pressure to agree to adoption. The forced placement of adults in “poorhouses”, “correctional labour institutions” or psychiatric clinics was also a common form of compulsory social measure. The forced placement of adults and minors in closed institutions was referred to as “administrative detention”, meaning an official measure that was usually carried out without a court decision that seriously infringed their personal freedom. Furthermore, forced abortions, enforced sterilisation and compulsory medical and psychiatric treatment were among the interventions carried out in the context of compulsory social measures.

As persecuted minorities, Yenish and Sinti, as persecuted minorities, were also severely affected by these measures. The systematic removal of children, the deliberate destruction of family ties and the subsequent demise of the Yenish way of life are now recognised as crimes against humanity.

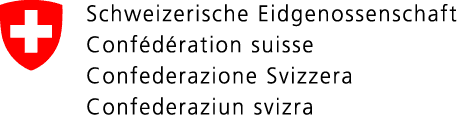

Placements were not always ordered by an authority. Many parents in need were forced to place their children in a home or give them away to work, or they were pressured by influential people close to them, such as priests, to agree to a placement. Poverty was widespread and highly visible in Switzerland until the second half of the 20th century.

Young women working in the fields at the reform school in Loveresse

Reform school for abandoned girls in Loveresse (BE). From the photo albums of the Bern Canton Welfare Authority, exhibited at the 1914 National Exhibition in Bern. (Author unknown). State Archives of the Canton of Bern, StABE T.1091, volume 2, image number 79

Image: unknown. Source: Staatliche Erziehungsanstalten: Maison d'éducation pour jeunes filles abandonnées à Loveresse. Zitierung: Staatsarchiv des Kantons Bern, StABE T.1091, Band 2, Bildnummer 79.

Roots in the cantonal poor law of the 19th century

The roots of compulsory social measures can be tracked back to the cantonal poor laws of the 19th century. These laws reflected the beliefs of the time about the most effective way to fight poverty. The 1857 Poor Law of the canton of Graubünden, for instance, stipulated that children could be removed from their families if they were receiving welfare (now known as social assistance) and, in the opinion of the authorities, were not being properly educated or cared for. Another example is the Canton of Bern’s Poor Law of 1884. Thia stipulated that adults could be committed to a “correctional labour institution” if they were deemed “slovenly”, “work-shy” or “addicted to drink”; the moralising and discriminatory language used at the time. In these institutions, people were expected to develop a “will to work” through duress.

Many people have experienced several compulsory social measures over the course of their lives. This practice was characterised by unpredictability and arbitrariness, and those affected often did not know when to expect an intervention. Families were frequently destroyed forever when their members were torn apart.

Expanded intervention options under the Swiss Civil Code

From 1912 onwards, the Swiss Civil Code (CC) was the main legal basis for compulsory social measures and placements. It empowered the authorities to remove children from their parents’ custody from parents and place them in foster care, as well as to place adults under guardianship or in “institutions”. Over time, such measures were increasingly ordered as a precautionary measure. For example, this might be ordered for a family who were not yet receiving financial support, but whom the authorities feared might require it in the future. As many cantonal laws were still in force, the legal situation became muddled.

The decision-making were often made up of laypeople who were not specially trained for their difficult task. Nevertheless, they had considerable latitude to make decisions and therefore held a great deal of power. Their decisions were rarely scrutinised. They often judged people and their behaviour according to moral criteria. For instance, they accused someone of being too “comfortable” to run a household properly. They overlooked the fact that some parents had only a low income and too little time for childcare and that high rents forced many families to live in cramped, unhealthy and dilapidated flats.

Bourgeois-patriarchal family model

The Swiss Civil Code was adopted by a parliament that largely favoured this model. Its members anchored this model in law. According to this model. the father was considered the breadwinner, while the mother was expected to take care of the household and children. This model also informed the practice of compulsory social measures: If a family man did not earn enough money, he could be sent to a “correctional labour institution”. Women were often judged according to ostensible “moral” criteria. For example, an unmarried mother, for example, was considered a disgrace in much of society. She and her children were seen as inferior. Furthermore, single mothers usually lacked the means to support themselves and their children, and there was a lack of childcare options. Children born out of wedlock were therefore often placed in foster care. Children from divorced families were also at great risk of being separated from their parents. Divorce was seen as a personal and moral failing. For this reason, the authorities frequently deemed it necessary to place the children, whom they labelled “divorce orphans”, in a home or with a foster family.

Authoritarian attitudes and social hierarchies

The authorities acted in a decidedly authoritarian manner. Adults were rarely asked about their needs; children and young people were scarcely asked at all. It was only in the second half of the 20th century that modern approaches to social work, based on a more equal understanding of care, were gradually established. Those affected also had hardly any legal recourse to defend themselves against compulsory social measures or placements. In a few cantons, it was possible to appeal to a court. However, research has shown that such cases were rare and rarely successful. There were various reasons for this. For example, those affected were unaware of the options available to them for lodging a complaint. They also generally lacked the financial means to hire a lawyer. Thus, inequality in society was perpetuated through the implementation of compulsory social measures. Rather than empowering those affected, they were often further marginalised and stigmatised. Social hierarchies persisted.

Who bears the responsibility?

Numerous individuals, public authorities and institutions were involved in the practice of compulsory social measures and placements. This included those who enacted the laws and those who made the decisions. The latter were often local authorities such as guardianship authorities. Institutions such as homes, “reform schools”, psychiatric clinics, and the numerous “child placement associations” (such as “Hilfswerk für die Kinder der Landstrasse” and “Seraphische Liebeswerk”) were also part of the system. Furthermore, ,many authorities also neglected the legal requirements for monitoring and supervising care facilities until well into the second half of the 20th century. Not only that, but under criminal law institution staff, or indeed parents, should have been prosecuted in the event of severe domestic violence or abuse. However, criminal proceedings were rare and far between. Even then, it was no guarantee that the victims would receive justice. The courts could just as easily rule against the victims. In many cases, close personal ties prevented an independent perspective. The churches also played a central role. They ran facilities and provided staff for homes or “institutions”. Regarded as moral authorities, they supported practices of coercive care. Research findings also show that strict moral standards and church structures facilitated abuse and cover-ups. The general public is also responsible, having long stood by in silence or looked the other way.

Decline in compulsory social measures after the Second World War

The first half of the 20th century was particularly characterised by conservative and authoritarian attitudes, economic crises and poverty. There was a widespread lack of statutory social protection in the event of illness, accident or unemployment. Consequently, a large number of compulsory social measures and placements were introduced during this period.

However, in the second half of the 20th century, the number of such measures steadily diminished. The decline was due to the unprecedented economic upturn after the Second World War, the introduction of new social insurances (such as the old-age and survivors’ insurance/OASI in 1948), and the expansion of outpatient assistance and counselling services. Foreign labour played a key role in the economic boom. While the living conditions of many Swiss gradually improved, immigrants were now increasingly affected by repressive family policies. Many families were torn apart because children were not permitted to enter Switzerland, meaning they had to live here in hiding or in children’s homes.

It is no longer possible to determine how many people in Switzerland were affected by compulsory social measures and placements. Research suggests the figure may be several hundred thousand.

The 1970s: changing values and the expansion of fundamental rights

It was a period of heightened upheaval for the implementation of compulsory social measures. New social movements in various areas of society questioned traditional authorities and power relations. Patriarchal gender norms were criticised, and women’s suffrage was introduced in 1971. People called for greater diversity and freedom in lifestyles. These social upheavals led to the formations of groups, such as Heimkampagne and Aktion Strafvollzug (ASTRA), which criticised the practice of detention in closed institutions. These groups denounced outdated structures and degrading penal practices, as well as forced labour in “reform schools”, prisons and psychiatric wards. Organisations campaigning for the rights of people with disabilities also became active.

A major milestone was Switzerland’s accession to the European Convention on Human Rights ECHR in 1974. The ECHR prohibits the arbitrary detention of individuals on vague grounds such as the imminent need for care. The regulations also stipulate that any person who is deprived of their liberty must immediately be informed of the reasons and have the order for this measure reviewed by an independent court. In order to implement these requirements, Switzerland introduced standardised regulations on the deprivation of liberty (and, from 2013: involuntary placement) in inpatient facilities in the Swiss Civil Code in 1981 (thereby enacting them at the federal level).

The law relating to children in the Swiss Civil Code was also modernised in the 1970s. From 1978 onwards, for instance, unmarried mothers were granted custody of their children. However, it would be several years before the law on the protection of adults in the Swiss Civil Code was revised.

Woman on a ladder covering up a poster by opponents of women's suffrage, 1969

The photograph was probably taken during the ‘March on Bern’.

Image: unknown. Source: F Fc-0003-39, Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv.

Protesters with banners against the penal system

During the 1st May rally in Bern in 1976, Marktgasse Bern.

Image: Hansueli Trachsel. Source: @ Flavia Fall, fotoCH, photo ID: 150514.

Transparent ‘Against lethal psychiatry’, 1980

Person at the AJZ (Autonomous Youth Centre Zurich) paints a banner with the slogan ‘Against deadly psychiatry’, 12 July 1980

Image: Gertrud Vogler. Source: F 5107-Na-10-058-012, "Jugendbewegung, 12.07.1980" - Transparent "Gegen die tötende Psychiatrie"; AJZ, Zürich, Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv.

Path to the present

The provisions that replaced the 1912 law on the protection of adults came into effect in 2013 under the name “Child and Adult Protection Law”. A key change was that, following its adoption, the cantons could no longer rely on authorities to decide on measures; instead, committees made up of professionals from various fields were established.

Another milestone in the strengthening of children’s rights was the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child of 1989, which Switzerland ratified in 1997. The convention calls for children to be protected from abuse and exploitation, and for them to be taken seriously as independent individuals.

The history of compulsory social measures and placements shows that it was once widely accepted that certain people’s personal rights could be severely restricted. These individuals were placed under guardianship and controlled in order to fight poverty and establish order in society. A fundamental tension between providing help and exercising control still characterises social work to this day. It is essential to scrutinise this repeatedly and to reflect on it professionally. Another important question is what we can learn from the past breaches of personality rights for our present-day approach to fundamental and human rights.