Criticism and resistance

Compulsory social measures and placements have repeatedly been the subject of public criticism over the years. For a long time, however, these were mainly the critical voices of individuals, who were unable to effect major change. It was only at the beginning of the 1970s that a broad public discourse began to emerge, as the mass media increasingly reported on criticism of homes, laws and official practices. Even the resistance of those directly affected long did little to change the difficult circumstances they faced. When their voices were finally listened to, this became an important precondition for the reappraisal that is now taking place.

Abuses in institutions and the lack of rights to a proper defence

One of the first and most important critics of the former care system was the writer Carl Albert Loosli (1877-1959), who himself had grown up in homes. As early as 1924, he called for the institutions to be abolished in his book “Anstaltsleben”. In another book and several articles in the 1930s, Loosli also denounced “administrative justice” as a violation of human rights. His criticism was perceived as a provocation by the societal elite. Nevertheless, from the 1940s onwards, it became the prevailing opinion in legal circles that the “administrative compulsory measures law” was in need of reform. Criticism focused particularly on the fact that the persons concerned were denied fundamental rights of defence and ways of filing complaints.

Others also publicly criticised abuses in the institutions from the 1930s onwards. Newspapers reported on violence, exploitation, sexual abuse and even the tragic death of a foster child. The abuse of children and adolescents also gained public attention thanks to reports in illustrated magazines. The best-known images were made by Paul Senn (1901–1953), whose reporting depicted rural life and people who were normally not in the spotlight. At the same time, photographs were also used for propaganda purposes to portray families’ destitute conditions as problematic. Well-known Swiss photographers were commissioned by Pro Juventute, for example, to take pictures of Yenish children and their families. The majority of these denigrating reports were intended to convince the population of the necessity of removing the children.

Sluggish reforms and public protests

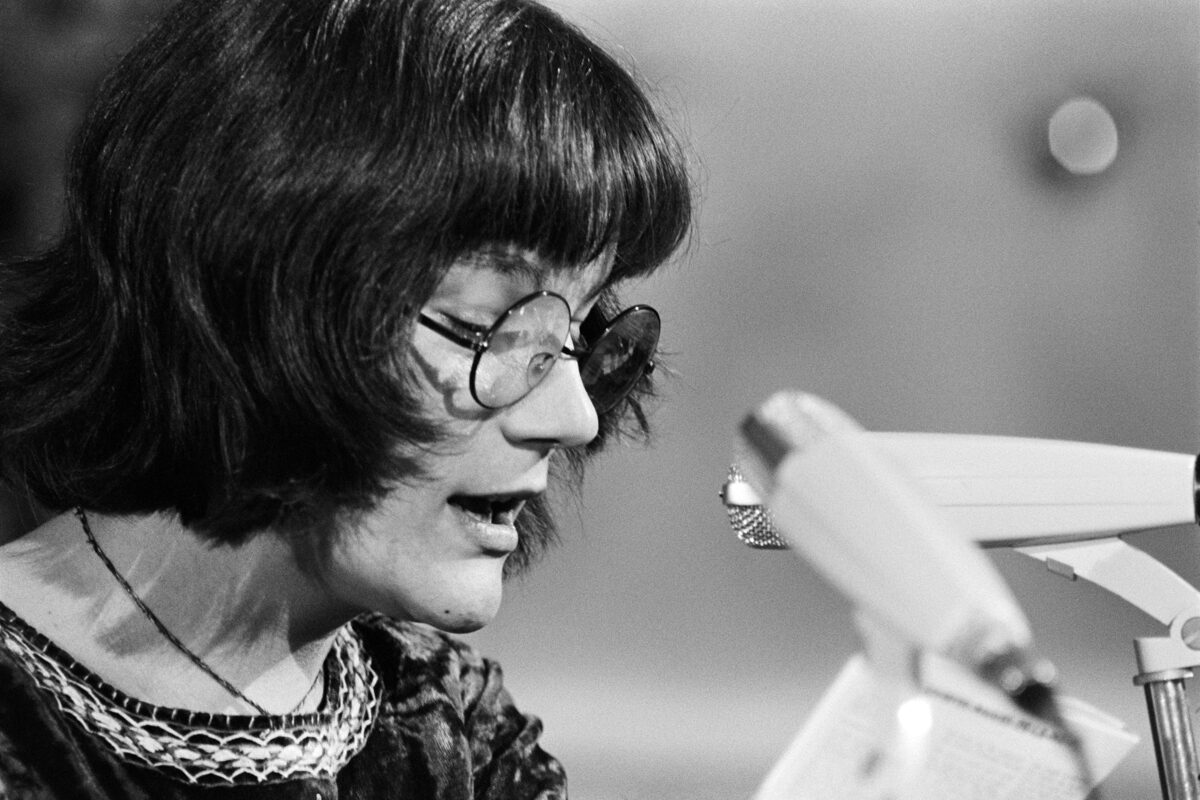

There were persistent voices that dismissed the structural shortcomings in the foster care system as tragic individual cases and the misconduct of individual actors. Increasingly, however, critical views from experts such as child psychiatrist Marie Meierhofer (1909–1998) gained attention. Based on her research in infant homes in the 1950s and 1960s, she found that infants in these homes developed severe symptoms of neglect.

Criticism of the foster care system and of other measures ultimately led to legal and institutional reforms. As early as the 1950s, associations such as the Schweizerische Pflegekinder-Aktion were founded to address abuses. Nevertheless, change was slow. Specialists called in particular for better training and remuneration for staff, as well as more funding for institutions.

Ultimately, it was the social upheavals of 1968, the emergence of the mass media and the influence of international debates that enabled proper scrutiny of public agencies and other authorities. “Reform schools” came under fire and made the headlines in various news publications. A social movement emerged in Switzerland at the beginning of the 1970s, just as it had previously done in Germany. The “home campaign” (“Heimkampagne”) sought to improve the situation of young people in homes through public protests and sometimes spectacular liberation actions. But despite this and their own resistance, the situation only changed slowly for the affected youths.

Marie Meierhofer at the institute named after her, the Marie Meierhofer Institute for Child Research (MMI), on the occasion of her 75th birthday in 1984.

Resistance by those affected was associated with major risks

There had always been affected individuals who defended themselves with words, attempted to flee or went on hunger strikes. Others wrote letters, lodged complaints and instructed lawyers to file appeals. But their arguments were seldom listened to, or even seen as obstinate behaviour. Those who defended themselves the could expect penalties. At the same time, there was little prospect of an improvement in their often precarious situations, as their files document and as they tell us today.

Legal protection in Switzerland was inadequate for a long time. As a rule, the appellate authorities ruled solely on the basis of the files and consultations with the authorities. In most cases, they did not carry out their own investigations and generally upheld the decisions of the lower court. There was also little solidarity with disadvantaged people. Those affected often had few resources. They were not aware of their rights and usually also lacked the financial means to obtain legal assistance.

Unsuccessful interventions

A lawyer and politician, the Graubünden social democrat Gaudenz Canova (1887–1962), repeatedly stood up for those affected, demanding that their human rights be respected. He was sharply critical of psychiatrists. He argued that their reports arbitrarily declared patients to be “mentally ill” and “in need of permanent internment”. However, his efforts were often unsuccessful due to the deference given to medical. The situation was similar for the less well-known people who, in many cases, volunteered to help those affected, such as social workers, pastors, lawyers and others. They had to reckon with slander and personal attacks.

Long struggle for a reappraisal of the injustices

It took a long time before those affected were not only heard, but actually had their statements taken seriously. Increasing numbers of them came to hold the state responsible for the injustices and the suffering inflicted on them. One of the first was the Yenish writer, journalist and political activist Mariella Mehr (1947-2022). She not only unsparingly depicted the violence she had experienced in her books but also demanded that those responsible recognise the Yenish people as a minority in Switzerland and acknowledge the injustices perpetrated against them. In the 1980s, the federal government began to support the reappraisal of the injustices committed against Yenish and Sinti people and the protection of minorities.

Since the 1990s, more and more people affected by compulsory social measures and placements have come forward, publicly speaking out on behalf of the many others who experienced unimaginable suffering through authorities’ interventions in their lives. It is thanks to the tireless commitment of those affected and the organisations they formed that both the general public and political decision-makers finally took notice of the injustices and suffering they endured. The personal efforts of those concerned were often draining and in many cases associated with further stigmatisation and social exclusion. However, their testimonies and reports demonstrate clearly that these were by no means just isolated cases and they laid the groundwork for a comprehensive reappraisal at the national level.